This is part three of my series of posts that explore the Javascript and Ruby object models. The goal of this series is to introduce the fundamental concepts of both languages by demonstrating their similarities and differences. If you haven’t already, I recommend you check out parts one and two which attempt to describe what objects are and how they are created.

For this part, I was originally going to talk about Javacript’s prototype system and compare it to Ruby’s class system, but found that was too heavy to take on in a reasonably sized blog post. Instead, I’m still going to talk mostly about Javascript’s prototype system, but show how Ruby can do something similar and at the same time introduce singleton classes, a pretty cool feature of the Ruby class system.

Property resolution in Javascript

We saw in part two that Javascript has the prototype property on all Function objects.

function Person() {}

Person.prototype = {

name: "anonymous",

say: function(msg) {

console.log(this.name + " says " + msg);

}

};

var person = new Person();

person.say('hello');

=> anonymous says helloBy default, the prototype property points to a plain object. You can add

properties to this object to give any new objects created from this function

some behaviour or data. Notice I intentionally did not specify a name property

on the person object, to show that it uses the name property on the

prototype.

Below is an alternative way of creating a new object, using Object’s create

function (introduced in Ecmascript 5):

var person = {

name: "anonymous",

say: function(msg) {

console.log(this.name + " says " + var);

}

};

msg adam = Object.create(person);

Object.getPrototypeOf(adam);

=> {

name: "anonymous",

say: [Function]

}This is a little bit of syntactic sugar around the cumbersome way of creating constructor functions and molding the prototype object.

We will miss out on some type checking goodness if we adopt this way since

person is created from the Object constructor (not the Person

constructor). Or quite simply, we can’t do this:

adam instanceof Person

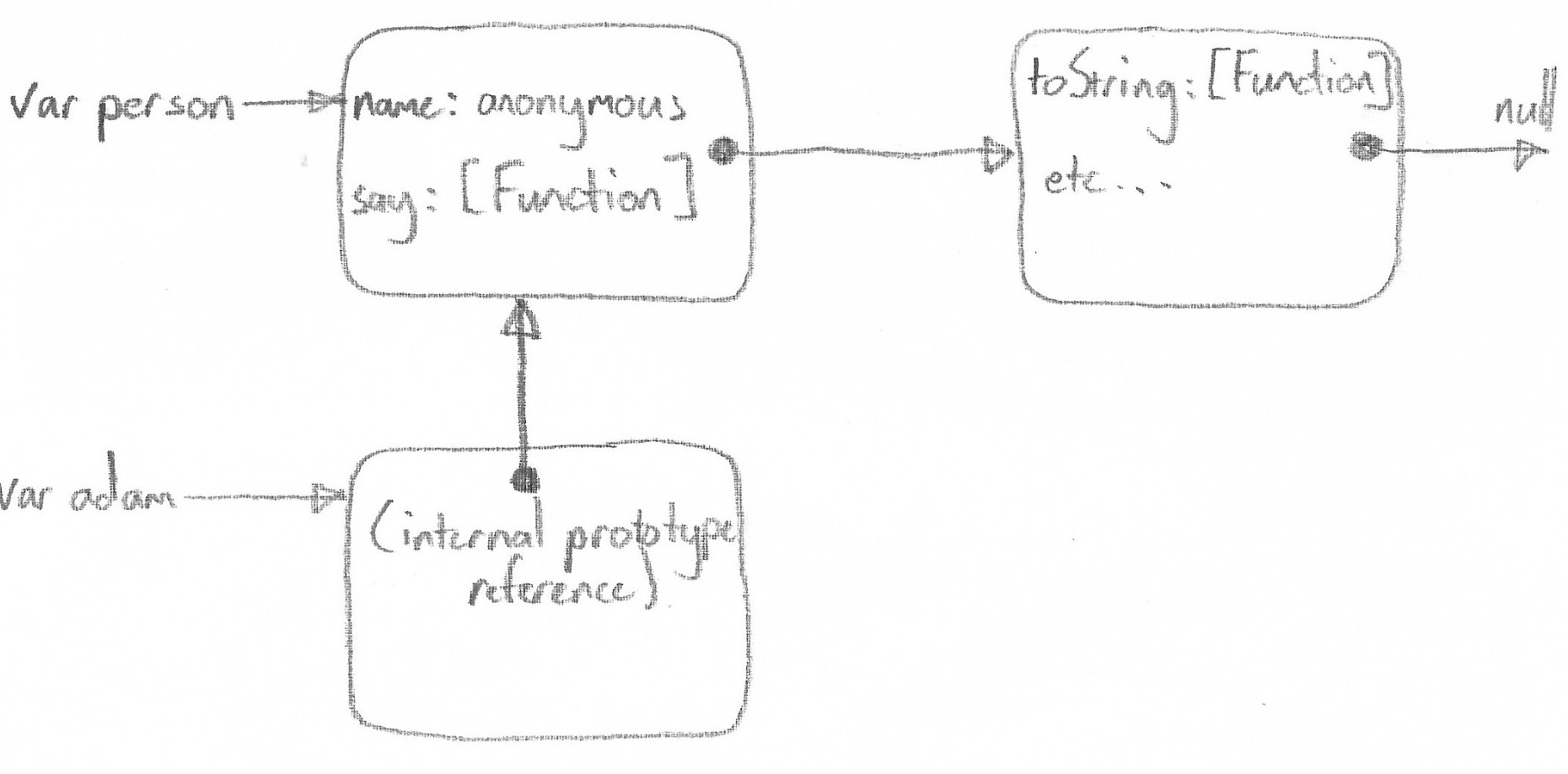

=> trueThe important thing to realize is that the person instance (shown above) now

has an internal reference to the prototype object. Since I did not define a

name property on person, it will first see if it exists on the local

object, and since in this case it doesn’t, it will traverse the prototype chain

until it is found. Because it exists on the most immediate prototype object,

it will return anonymous. This is in a nutshell how property look ups work in

Javascript.

Here’s a diagram:

To illustrate further:

Object.getOwnPropertyNames(person);

=> []will not list name. This function lists all properties that are local to the

simple object only. It does not traverse the chain of prototypes.

However, if we do this:

person.name = "Adam";

Object.getOwnPropertyNames(person);

=> ["name"]

person.name;

=> "Adam"we are defining a property on the person object called name. You may think

that this is overriding name in the prototype object, but it is actually

defining a new property on person, the local object. The property lookup

will find it immediately on person and will have no need to traverse the

prototype chain. If we delete this property:

delete person.name;

person.name;

=> "anonymous"the name property no longer exists on the local object, and therefore is

looked up on the prototype object and found there. This illustrates a clear

distinction between the local and prototype objects, where the prototype is

like a fall back if a property is not found on the local.

However, if we did this:

person2 = Object.create(personPrototype)

delete prototype.name

person.name === undefined

=> true

person2.name === undefined

=> truethe two objects that reference the prototype object can no longer find name.

Prototypes in Ruby?

In Ruby, we can take advantage of some interesting features of the language to implement the prototype pattern, even though it’s not something you would commonly do.

# create a person object

person = Object.new

# define some behaviour for person

def person.name=(name)

@name = name

end

def person.name

@name || "anonymous"

end

def person.say(msg)

"#{name} says #{msg}"

end

# create a new person by cloning person

adam = person.clone

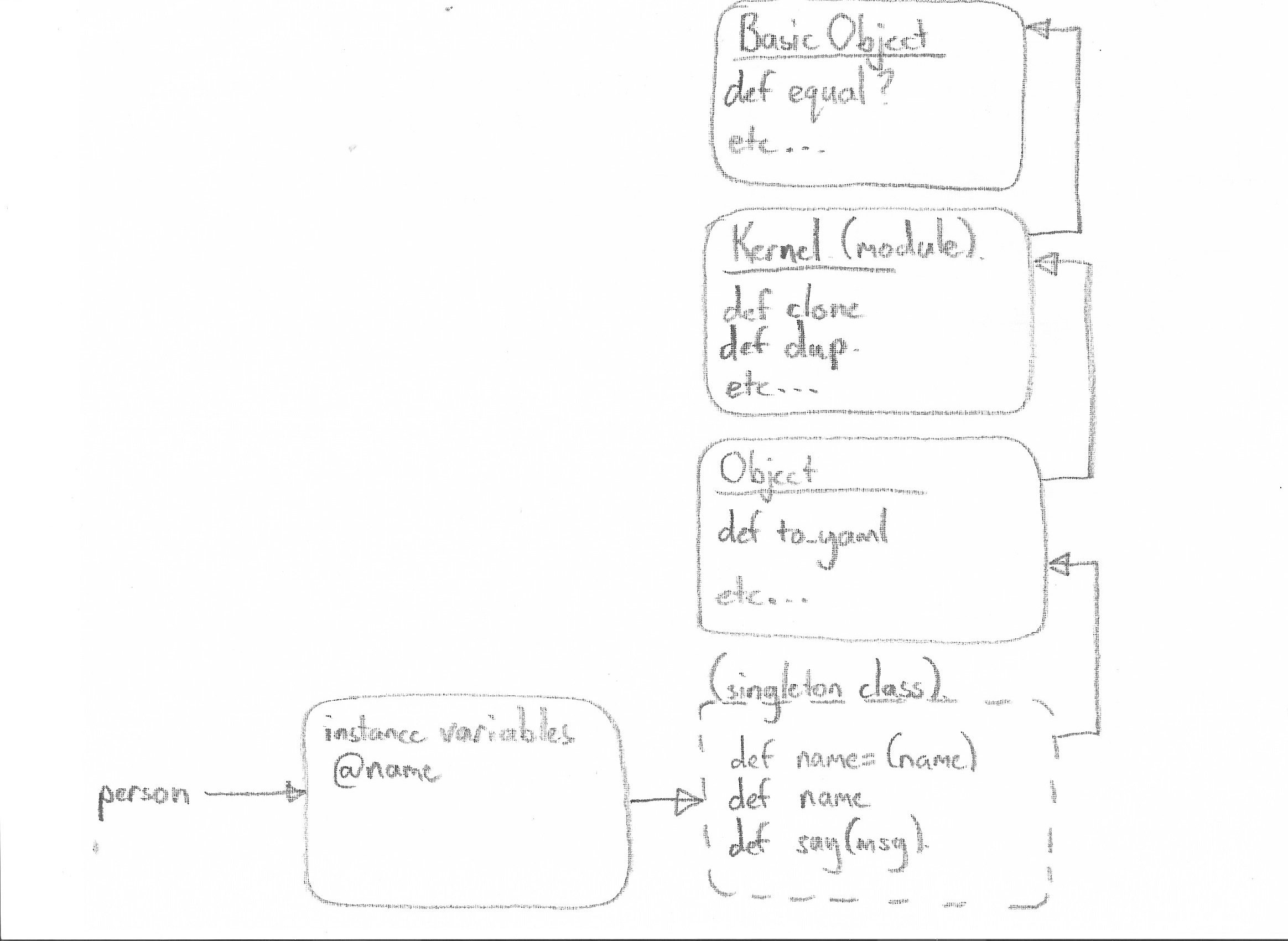

adam.name = "Adam"Notice there is no class definition here to define behaviour. You may think that

the above code is circumventing Ruby’s class system, but what we’re really doing

is opening the object’s singleton class and adding behaviour to it.

Singleton classes in Ruby are an important concept that allow you to add ad hoc

behaviour to an object. This class is placed at the head of the ancestor

chain. Because person is created from the Object class, the singleton

class’s super class is Object.

person.singleton_methods

=> [:name, :name=]

person.singleton_class.ancestors

=> [Object, Kernel, BasicObject]

person.class

=> ObjectNotice that you call class on person, it still returns Object. The

singleton class is unseen in this case which is why some folks refer to them as

ghost classes.

The disadvantage of this approach is that we have no meaningful way to do type

checking. The adam object is always an Object, but how do we check that

it’s a person?

adam.singleton_class == person.singleton_class

=> falseThe reason why the above returns false is because the singleton class is also

cloned ie, adam and person refer to two different singleton classes with the

same behaviour. This demonstrates an important thing about singleton classes,

that all objects get their own singleton class.

You probably would not want to create your object relationships in such a way in Ruby but you can see some parallels here with how prototypal inheritance works in Javascript.

Ruby Methods are really just message handlers

Ruby uses a paradigm of sending a message rather than the common paradigm of calling a method.

str = 3.to_s

#is the same as...

str = 3.send(:to_s)You can imagine the message (method call) is sent along a message bus (the

class hierarchy). If we consider the diagram above, the message bus is the

class hierarchy, starting from the singleton class object all the way to the

BasicObject class object. A message is captured and handled if one of the

classes in the hierarchy has a defined method of the same name as the message.

If no method is found in the hierarchy, than a NoMethodError is raised. Notice

this method of sending a message along a bus in the hope that it will be

handled is very similar to how property resolution occurs in Javascript by

traversing the prototype chain. A key difference however, is that if it’s not

found, it is handled by a private method on BasicObject called

missing_method, which will actually raise the NoMethodError we just talked

about. You can override this to do you’re own method missing handling.

Summary

Javascript’s prototype system is rather straight forward and can be thought of

as a linked list of objects. The process of resolving a property starts on the

local object and works all the way down the chain until you reach the Object

prototype, which is the end of the line. Javascript’s simple object model is

offset by its awesome functional component (which is out scope for this series

of posts), and this is where Javascript’s magic lies.

Ruby’s magic on the other hand, is with it’s class system, which was too much to cover in this blog post. Instead we demonstrated that we could setup a similar prototype system using Ruby, demonstrating singleton classes as a result. You obviously wouldn’t use this pattern as a day to day tool, but it’s interesting to find the parallels. We also introduced the idea that Ruby broadcasts messages along a class message bus. And that method definitions are simply message handlers that could be stationed anywhere along that bus.

We have arguably covered most of the similarities between Ruby and Javascript. But we still have yet to talk in detail about Ruby’s class system, which we will cover in part four. This is where we will show where Ruby’s class system differs from Javascript’s prototypal system.